The second period of Sumerian history is called the Uruk

Period (4100–2900 BC) and is marked by

the emergence of the world’s first cities.

Part A

Characteristics

of a ‘City’ and ‘Civilisation’

The term ‘civilisation’ simply comes from the Roman word for city, but even in Roman times 'being ‘civil’ acquired a value judgment (of being a good Roman citizen).

|

| Restored Ziggurat of Ur |

In sixteenth century France (in a world on the edge of the 'Age of Enlightenment') ‘being civilised’ acquired other value judgments : indicating sophistication, good manners, rationality, enlightenment and ‘superior’ behaviour (as contrasted with a more ‘primitive' society).

This can cause some confusion, but remember, for the noun (especially in Archaeology, anthropology and related disciplines) pare back the value judgments: it simply refers to a culture that has built cities.

It may not sound dramatic as the more nuanced adverb, but cities and urbanisation are a quantum leap forward in social organisation.

But what defines a city (in the ancient world) rather than a large agricultural community?

Childe, in the 1936 book (and later) defined a list of

characteristics which included size and population density, sophistication,

specialised workforce, taxation, monumental building, ruling class, symbolic

representation, science, sophistication and organisation beyond kinship.

Characteristics

of Urbanisation

To simplify somewhat: a city (urbanisation) is characterised

by a large specialised central settlement inside of which much of populace is not directly involved

in producing food.

It requires and is characterised by several things:

1. A significant, available, food surplus.

Each city has to be closely connected to agricultural towns, farms, fishing villages and herding camps that supply food and other resources to the city, in exchange for finished goods and services.

Sumer, at

its height, was the most agriculturally productive region in the world, serviced

by complex irrigation and transport canals and it supported previously

unheard of population density.

2. Stratified

society.

In the city there is a full-time bureaucracy, military, a stratified society and complex industry. The specialisation allows economies of scale and more rapid advances in knowledge.

3. Transport

Transport aids the free flow of goods and services. Sumer was well serviced by canal transport. Uruk had such an extensive network of canals it has been called the ‘Venice in the desert’.

Since the Ubaid times Sumerians had oxen carts. The donkey was a very welcome addition, arriving in the middle of the Uruk period.

Sophisticated trade cannot occur without some form of currency.

From Palaeolithic times humankind used commodities as the first currencies.

This is sometimes confused with barter but here, individuals

(who are not traders) accept a well recognised commodity which has an understood value as a means of exchange. And they are prepared to do so in quantities beyond what they need for personal

consumption.

Cattle or other livestock was currency for expensive items such as a (noblewoman’s) bride price, or to build a defensive tower across a range of cultures.

Flint,

obsidian, metal, beads, shell -jewelry, axe heads, salt and rum have all been

used at various times throughout human history.

Metal had to be imported into Sumer and didn’t come into its own until a later period. The predominant commodity used during the Uruk era for large purchases was grain.

Other commodities were used for smaller purchases. (In

a later period, there is even the record of payment to a labourer in beer.)

5. Records and

accounting

How can grain be used as a currency? Did the Sumerians carry bushels of grain around to pay labourers?

If not, how did they make payments? The answer (at least for

significant purchases) was the token system.

Tokens arose during the very beginning of the Neolithic period, paralleling the cultivation of grain and communal storage. If a landowner was to deposit his surplus of grain in a community warehouse, he would definitely want some record of what was his!

The first examples of this in Northern Mesopotamia date back to 9,000 BC in the earliest Neolithic times.

Stamp seals (carved in stone to be pressed into wet clay) were invented soon after, as a type of

official signature. This technology was brought to Sumer with the first Neolithic farmers and irrigators.

During the Uruk period (5 millennia later) tokens and seals continued to evolve into a complex accounting system.

There was never any

need to lug bulk grain or other commodities around. Any large transfer of

ownership was achieved by the token system, a bit like transfers recorded within a bank, but in this case it was administered through the community storehouse under the control of the priestly class.

The centre of the community at that time was the temple. The leader of each city-state and its surrounding lands and towns was a king/priest.

Priests and their acolytes were not only responsible for religion and holy ceremonies they were in charge of higher learning, taxation, records, administration and running the communal

granary.

The increasing use of symbols

Over time, different tokens were used until they covered something like sixteen important commodities.

(Counting) tokens to aid calculations were then introduced

. A small cone denoted 1, a ball was 10, and a large clay cone was 60.

Special round clay containers (bulla) were designed (like a lock box at a bank) to preserve a collection of tokens held inside. They could only be opened once (to prevent tampering).

As these containers had a record of the contents and personal seals on the outside, it led to simple clay tablets being used, instead, for simpler records.

Soon after, the Sumerians invented symbolic representation

of numbers (with the main base 60) to further assist with accounting and their solar

calendar.

The whole system was becoming too cumbersome as society

and trade became more complex.

Pictograms, the world’s very first form of writing

The need for Sumerians to represent more complex concepts led to the world's first true form of writing (pictorial writing) around 3500 B.C

.

Pictographs (picture words, and petroglyphs) in simpler

forms date to Paleolithic times.

Sometimes a ‘determinative’ was added (a symbol which

specified semantic class) which meant the same symbol could be used for a range

of items or concepts.

Drawing curves on clay is difficult, and the Sumerians

soon began experimented with a range of writing systems (often concurrently and

often combined).

As Sumerian writing predated Egyptian writing and the

Egyptians did not show this phase of experimentation, it is generally accepted

that it was the Sumerian writing that inspired Egyptian hieroglyphics.

Cuneiform, one

of the world’s Great writing systems

‘Cuneiform’ writing emerged around 3400 BC.

Its name means ‘wedge shaped’ and it involved a wedge

shaped stylus, elimination of curves and the use of highly stylised symbols.

The writing also became from left to right (not top to bottom as before).

Cuneiform writing became amongst the greatest writing

systems in antiquity. It lasted through to 100 AD. with many adaptations. It was eventually used for writing fifteen languages.

Why was cuneiform so successful, apart from its specific adaptation

to clay tablets?

It became phonetic, or at least partly so.

Sumerian was mostly monosyllabic. If you ignore the

accents, a lot of words are spelt the same way (they are homonyms). So the Sumerian šu

(“hand”) could stand in for a lot of similar sounding words.

Also (in keeping with pictographs) a symbol could stand in

for a series of related but different-sounding words “sun,” “day,” “bright” further reducing the number of symbols needed.

Semantic ‘determinatives’ continued to be used to keep the

number of symbols within reasonable bounds, and pictographs continued to be used

for names.

|

| Contract for the sale of a field and a house |

It was finally displaced by alphabets (or at least the consonant-only 'alphabets', like Phoenician writing, that we call ‘abjads’ ).

These ‘alphabets’ were first invented by a group of Semitic workers and traders living in Egyptian- occupied lands of the Sinai and south Canaan around 2,000 BC.

Vowels were later added to reduce ambiguities.

Alphabets were originally designed for writing on papyrus and parchment (with ink).

When they are carved (e.g. wood or stone) with ancient technology, the characters have to have a more angular shape (which incidentally is one of the reasons runes were developed around 150 AD by the Norse and Germanic people) .

Papyrus was easier to use than clay tablets but, perhaps almost as importantly, alphabets were so much simpler

to learn and use.

There were attempts to simplify cuneiform writing. The best was by the clever Persians during the Achaemenid Empire (550 BC–330 BC). They used a cuneiform alphabet with 36 phonetic characters (including vowels) and 8 logograms.

But by this time the use of cuneiform writing was passing and the Old Persian characters were eventually abandoned.

Even though writing emerged in the late Uruk period, we have scant written records from this time.

The whole period is sometimes called the ‘proto-literary’ period because it was characterised more by the increasing use of symbols that led to the emergence of writing.

Tokens would become almost obsolete. Contracts, vouchers, payrolls, accounts and private ownership was all recorded on clay tablets.

Some of

these were intended as temporary records, but there are something like tens of

thousands of Sumerian and other tablets in the back rooms of museums around the

world, some not yet not fully translated. It is only a fraction compared to what has been lost.

First

urbanisation

Most will accept that world's first urbanisation was achieved early

in the Uruk period (4100–2900 BC).

For reasons already explained, archaeology is difficult in Sumer. Wood and stone were in short supply and most construction was mudbrick. There was a tendency to recycle and build on top of older layers. The oldest ruins ended up deep under layers of silt and overlain by more recent, but still important, archaeological remains.

In what became one of the most important city in much later times, Babylon, archeology is further hampered by its high water table.

But wasn’t there

cities in the Neolithic period?

No. Some people have been tempted to claim certain Neolithic settlements as the world’s first cities. One example is Çatalhöyük in Turkey, but it never achieved urbanisation.

|

| Çatalhöyük |

Jericho.

Jericho has also been suggested as the world’s first city or 'the world's oldest continually occupied settlement'. Unfortunately it is neither.

|

Jericho has several periods when it was abandoned, and so it fails the test for the

world’s longest continuously occupied settlement as well.

For instance, it was completely destroyed maybe in the 17th or 16th centuries BC. (Likely by the Egyptians).

Ahmose I defeated the Canaanite ‘Hyksos’ (foreign rulers of northern Egypt) around 1550 BC. and then campaigned as far as Byblos in Lebanon.

A reasonable assumption is that he expelled many Canaanites from Egypt (or they fled before his armies), perhaps inspiring the Biblical story of the Exodus.

A small unwalled settlement was rebuilt there in the 15th

century BC but it was soon abandoned and Jericho is said to have been empty till the 10th/9th centuries BC. despite historically inaccurate claims that the Israelites under Joshua sacked it (probably in the mid-late 13th century BC).

Was Eridu the

world’s first city, then?

In Sumerian tradition the old port city of Eridu was Sumer’s (and hence the world’s)

first city.

It was very well favoured, being well suited for irrigation, near the sea for food and trading, handy to marshes (for fish, birds and other resources) and close to herding activity.

Unfortunately for Eridu, the sea later marched (a considerable distance) south under the influence of silting and falling sea levels (in the first thousand years), all made worse by the shallow fall of the land.

The low basin where it was situated was especially prone to flooding and Eridu's fortunes fluctuated considerably. It was abandoned at times, but estimates of when this was vary enormously.

One gain from its growing distance to the sea was a massive expansion of the nearby marshes which (during the flood season) formed a giant lake the size of Galilea.

|

| Sumer , with new coast line (Wiki) |

Max Mallowan described Eridu as an 'unusually large city' of ‘not less than 4000 souls’ covering 8-10 ha (20-25 acres) during the Ubaid period. Kate Fielden alternatively suggested it reached this size ‘by 2900 BC’.

These estimates are over a

thousand years apart ,showing just how murky our knowledge of this period is and how different estimates often contradict each other.

A more important question is, how a settlement of considerably less than 10,000 be called a ‘city’?

It was not likely.

Uruk, the

favourite contender

In Sumerian legends Inanna, the young (but mischievous)

patron Goddess of Uruk, challenged her father, Enki, to a drinking competition.

While he was drunk, she tricked him into giving her the important ‘Mes’ (the essence of civilisation) which

she took from Eridu to Uruk.

The Mes’s form and characteristics were not specified, though it had some sort of physical form because she was able to put it on display. It was also sometimes called a (minor) God in its own right.

It included the knowledge, institutions, technology, laws and culture (anything that the Sumerians thought made civilisation possible).

It seems the Sumerians believed the main civilising force had

passed from Eridu, the important settlement of Ubaid times, to Uruk, the star of the Uruk period.

Uruk was long the most impressive of all Sumerian cities, establishing cultural hegemony over a vast region.

|

| White temple and Ziggurat (wiki) |

It began around 5,000 BC. and soon absorbed a neighbouring town, resulting in not one but two temple districts.

This included, in the late Uruk period the erection of a great white temple on top, plastered with gypsum. This was 20 metres above the city and would have been able to be seen from a great distance. .

The second temple district, Eanna (500 metres away) had more modern temples and monumental buildings. Between the two were busy workshops and residential districts.

Throughout the whole period, which bears its name, Uruk grew rapidly. Unfortunately, the time periods are extremely imprecise with competing estimates but it seems to have reached urbanisation sometime in the early Uruk period.

By 3700 BC it was said to have reached between 175–250 ac (70–100 ha).

It was later than this, but still during this period, the culture of Uruk (and urbanisation) began to spread to other sites.

Uruk eventually managed to expand its sphere of influence as far as Upper Mesopotamia, northern Syria, western Iran and south-eastern Anatolia.

The greater region and its surrounds was not exactly the one culture, there were regional difference and differences in language in places like Elam and Northern Mesopotamia.

By the end of the period, Uruk had reached 40-50,000 citizens

with 80,000-90,000 in its surrounds.

Tell Brak, a

little known contender (as the world's first city)

A team of American and British archaeologists surveying

Tel Brak in Syria, believe they have found the world’s first city, and it was in Syria (Upper

Mesopotamia) instead of Sumer.

They published (in 2011) the culmination of over thirty

years work and publications.

The original name of the city is unknown but it was later called Nagar. It was founded during the earlier northern Halaf culture. Situated on a river crossing between Anatolia, the Levant and Sothern Mesopotamia it became an important trading and manufacturing hub absorbing the earlier ‘northern Ubaid’ culture.

During the Ubaid and Uruk period, its growth mirrored that

of Sumer and it became the largest city of Northern Mesopotamian at that time.

At the start of the Uruk period Tell Brak was already 55 hectares.

It was bigger than Nineveh, back then known as Ninua, not far from Mosul in northern Iraq.

Nineveh was destined to become the world's largest city around 700 BC but back then it came in second to Tell Brak at 'only' 40 hectares.

By the end of the Uruk period 'Brak' had reached 130 hectares, making it a serious contender with Uruk as the world’s first city.

Interesting this enclave was abandoned and levelled at the end of the Uruk period and the city suffered a significant contraction.

A similar but smaller city, Hamoukar, to the east was also destroyed around 3500 BC after a siege.

The culprits are unknown but most suspect a military expedition from Uruk. Civilisation had obviously brought the wonderful benefits of siege-warfare, looting and slavery.

And the winner

is?

It was in the early Uruk period that the world’s cities had begun to emerge.

Sadly, due to the problems of excavation in Sumer, it is impossible to decide if the first city was Uruk or Tell Brak.

It might be tempting to favour Uruk which continued to be the greatest city in Sumer for Millenia.

Whatever the answer, Sumer owed a great debt to the north that we have sometimes underestimated.

It was where many of the innovations began that allowed the settlement of Sumer.

Part B

The Sudden Collapse

Around 3100 BC. just when Uruk was at the

height of its power, it and the cities of Southern Sumer faced some sort of sudden catastrophe.

Uruk’s influence collapsed, long distance trade in and out of Sumer

dwindled to a trickle

The Uruk culture ceased, only to be replaced by the inward looking Jemdet Nasr Culture (3100 to 2900 BC ).

The Jemdet Nasr Culture had already been in the back water regions of Northern Sumer but now it extended its influence over the southern cities, even Uruk.

Settlements became less dense and hand painted pottery emerged, suggesting the end of cheaper mass production that was possible in Uruk times.

Exactly what happened politically during this period is

unclear but at the start of the next period (the early dynastic period 2900–2350 BC) hegemony had passed to the (northern) city of Kish which for a time controlled Uruk.

Kish was Akkadian (Semitic), part of the greatest minority group in Sumer.

Was it a Semitic invasion from the north?

No, they were already there

Archaeologists initially believed that the fall of Uruk was due to migration of Semitic people into the northern regions.

Ancient DNA shows they were there likely from as early as Mesolithic times.

It is harder to extract viable DNA from ancient samples in a warm climate, but recent studies show that the ancient (Semitic) natives of the Levant were distinct from the ancient people of Zagros (Iran) and Anatolia (Turkey). They were the three groups that would form the great Neolithic powerhouses.

Those in the Levant had connections with people of Arabia and north western Africa but had diverged from them by 13,000 BC or maybe even as early as 22,000 BC .

The bulk of the DNA for modern day Palestinian, Lebanese, Jordanians and Syrians (speakers of Levantine Arabic) comes from this ancient group.

There has been the addition of other DNA over time (which is not too surprising in such a busy corridor for people movement).

In other words, the ancestors of the ('Levantine') Semitic and related people arose in the Levant in Late Paleolithic times. They were part of the Mesolithic Natufian culture (beginning 13,000 BC).

It was they, in turn, who were responsible for the beginning of Neolithic culture (10,000 BC).

By 7,500 BC Neolithic culture had spread decisively across the whole fertile crescent including into what is now Syria, north of Sumer, giving rise to a number of Neolithic and then Copper Age settlements and cultures.

Rise of the Semitic Traders

We will come back to the fall of the Uruk culture in a minute but this is a good time to divert and briefly discuss this group.

Later, the 'Arabs' of the Gulf region were destined to become famous traders.

Now we can tell that their northern cousins were already in position in the Levant and northern Mesopotamia and had a central role in 'northern' trade from prehistory onwards.

They straddled the northern land route in and out of Egypt, the land routes between Sumer and Anatolia and the overland route to the Zagros region, Afghanistan and India.

Both Egypt and Sumer were great producers of grain, and became very wealthy, but were short of many natural resources like metal and wood. They often used reed boats.

The Semitic people of the Levant (ancestors to the Phoenicians and others) also had the cedar of Lebanon, and other sources of fine wood.

Also, encouraging sea trade, the eastern part of the Mediterranean was also particularly favourable, due to the combinations of winds, currents, and general topography.

So the coastal Semitic people became not only land traders, but the great sea traders of the Mediterranean achieving a dominance that would last millennia.

Sea trade can carry greater loads than land trade.

It was sea trade above anything else that really opened up Egypt to the grain markets of the ancient world and led to its great rise.

The Semitic people of the eastern Mediterranean dominated this sea trade through till the fall of Carthage to the Romans in 146 BC.

Coming back to the 'last days' of the Uruk period, these overlapped with the early Middle East Bronze Age (beginning 3300 BC.) by several centuries.

Bronze requires not only copper but tin which is relatively rare and the 'Bronze Age' is synonymous with complex, highly organised, trade.

Climate change

Other Invaders?

We don't have genetic studies closer to the time but modern Syrians show an influx of genes from the Caucasus and Zagros region. Our history tells us this was likely later, occurring during the time of Amorite Mesopotamia (see later blog)

No, the northern (Akkadian) part of Sumer recovered first and whatever happened had to be something particularly affecting the south, not the north.

The Uruk period saw the progressive loss of the ‘Indian’ Monsoon, especially affecting Arabia which continued to dry out. Settlements there withdrew to oases and favourable areas of the coast.

For the rest of the Middle East, the Uruk period was colder and wetter (under the ‘Piora Oscillation’ 3900-3000 BC.) Now many archaeologists postulate the Uruk culture fell due to a long dry spell, causing a rise in salination.

Was there something else as well?

Does the Great Flood Myth refer to a real event?

Climate change sometimes brings a period of climate instability, not just drought but interspersed with floods. The modern world has experienced this with our own recent climate change.

The Sumerians firmly believed the Uruk period ended with the Great Flood.

Of course, the Sumerians were not the only ancient people to have a flood myth, but it was their version that inspired many of the others including the Dravidians (Indians), the Romans, the Greeks ... and the Flood Myth in the Bible.

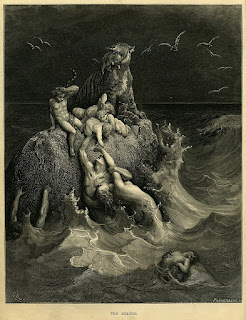

|

| Gustave Dore, Bible Illustration |

Sumerians have different versions of their flood 'myth'.

They all, like the Bible, include the tradition that their antediluvian leaders lived for many centuries.

The main Sumerian ‘Noah’ was called Ziusudra and was the leading priest/king of all of Sumer.

One later version bears a particularly uncanny resemblance to the Biblical story. In this, the ‘Sumerian Noah’ lands on Mt. Nisir, ( meaning ‘mount of salvation’, where-ever that was) rather than being was washed down to Dilmun (part of nearby Arabia in the Persian Gulf) as in other versions .

Most modern archaeologists do not take the idea of a great flood seriously.

They argue that if the flood was a real event we should have records mentioning closer to the time. The earliest mention dates to 1600 BC (Nippur)

Perhaps not.

Most versions of the ‘Sumerian Kings List’ mention the flood as the starting point (some give a list the mythical kings before the flood), so we can push this date back many hundreds of years.

It is also suspected that the original ‘SKL’ was written some time during the Akkadian empire (2334 – 2154 BC) but those copies have been lost, so that might get us a little closer.

After a great catastrophe (at a time when writing was only emerging and possibly followed by a time of cultural weakness in the South) it may not be surprising that we don’t have good records.

In fact, this sort of situation is not unique in archaeology.

One thing we know for sure about Sumer is that we have only recovered a small fraction of what was written, especially from the earliest of times.

Leaving written records to one side, other archaeological evidence shows there was not one, but several truly catastrophic floods between 4,000 and 2,000 BC.

Some of these affected different parts of Sumer and some happened after the period of written records and were recorded.

In 1964, Sir Max Mallowan

(eminent archaeologist and husband of Agatha Christie) was amongst

several archaeologists who pointed to one apocalyptic flood, around 2900 BC,

which fits the end of the Uruk Era.

It also involved a very large area in the south, with silt and interrupted

settlement at several sites.

If this was the ‘big one’ and the source of the myth, it wasn’t just a once in a thousand year flood. It was Armageddon, the end of the world. It was sent by the Gods to eliminate mankind.

Or at least that’s the way it must have seemed to the people of Sumer.

They were well used to damaging floods, their settlements had massive dykes and flood defences, but they would have been overwhelmed, ending up well under water.

Crops, livestock, livelihoods, important food stores and infrastructure would have been

gone.

They had plenty of reed boats, (canals were the main form

of transport after all) but its hard to

know how effective they were in such a massive flood, and the ensuing chaos.

Following the fall of the Southern cities of Sumer, it was the Northern (Semitic) cities like Kish, Jemdet Nasr and Akkad that were amongst the first to recover.

Not that the Flood Myths are anything like a historical account, but it is easy to believe such an event was imprinted on the Mesopotamian psyche with scars so deep that the legend lives on till today, five millennia later.

Whatever was the cause of the fall of Uruk, climate seemed to play a huge part.

The Sumerians had taken their inhospitable land and with massive labour and ingenuity had turned it into one of the most fertile places in Earth, but it was always ready to turn on them.

One thing about the Sumerians was their ability to recover, but even as they did, time was running out for them and their land.

I hope you have enjoyed this second blog on the Incredible Sumerians.

Part 3 of this 4 part series will look at the Early Dynastic Period' : Recovery, Kings and Emperors

I also write Epic Fantasy set in ancient times.

Please check out my Amazon Authors page here or at your favourite e-book store.

My first book : 'The Elvish Prophecy' is free. Universal link Click Here or Amazon Click Here

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.