Home Page home page

The Amorites (2 of 2)

The Ill Fated first Babylonian Empire

The Amorites were a rural group originating from the region north of Sumer.

They were comprised of contentious tribal (and sub-tribal) groups led by ambitious chieftains.

While they absorbed the Akkadian language and culture, they did not have the deep cultural beliefs in social order or in the veneration of cities and infrastructure that had kept Sumer peaceful and prosperous for so long.

They saw no problem with fighting amongst themselves, forming unstable alliances across tribes and even, for some, the destructions of the great canals on which life in Sumer depended.

After the fall of UR III, the Amorite dynasty of Isin was strong enough to keep peace in southern and northern Sumer for a hundred years.

But, this ended in 1926 or 1923 BC (middle chronology) when Larsa, under Gungunum, rebelled and captured Ur, plunging southern Sumer into civil war.

There was not only war in the south, northern Sumer was left open to the sorts of conflicts already occurring across the rest of Amorite Mesopotamia.

The (Amorite ruled) city of Kazullu (in northern Sumer) was one of the early losers in this period, finding itself attacked by several neighbours.

It lost land, and ultimately fell, to a man called Sumu-(Amorite for chieftain) Abum.

He established his capital at Kisurra but more importantly, the land he conquered (1897 BC Middle Chronology) included Babylon.

Babylon was at the time a small

town, the cult centre for Marduk (at the time a relatively minor deity but destined to

become the head deity of the Mesopotamian religious pantheon, as Babylon gained

in prominence).

Little is known about the next three ‘Babylonian’ chieftains who were busy defending their territory and expanding it (modestly) at the expense of their neighbours.

The greatest danger for them was attacks from the south (from Larsa and on one occasion from a briefly resurgent Isin).

Hammurabi’s father, Sin-Muballit, was more successful. He decisively repelled Larsa then steadily strengthening his kingdom into a significant (if somewhat modest) local power.

He transferred his capital to Babylon and was the first of his 'Babylonian' dynasty to take on the Amorite title ‘Sin’ (meaning king).

He retired due to ill health with his son, Hammurabi (Amorite: ʿAmmu-rāpiʾ meaning my grandfather, or paternal uncle, was great, or a healer), ascending to the throne at eighteen ( 1792 BC, MC).

At that time the geopolitical situation was complex and in a state of flux.

To the south, Larsa and Isin continued to struggle for dominance while several cities maintained

their independence.

To the East was Eshnunna. Eshnunna up until then was often a client state (most often of Elam) but a strong and clever local dynasty had more recently taken control.

They had managed to expand their territory and even

forced the Amorite king Šamši-Adad I to flee his home in Ekallatum (in what

would later become the Assyrian region) for Babylon.

Šamši-Adad I had subsequently returned and had proven triumphant.

He conquered the nearby towns that had been weakened by Eshnunnites (but not held by them).

He then used treachery towards his allies, war and even assassination to put his own son on the throne of Mari and make Eshnunna subservient to him.

This gave him an immense and rich kingdom, (‘The Kingdom of Upper Mesopotamia’).

He controlled the important East-West overland trade routes and even 'inherited' the ancient Assyrian trading colonies in Anatolia.

To the Northwest (of Babylon) was the large and powerful Yamhad Amorite tribe centred on Halab (modern day Aleppo) and its smaller rival Qatna.

Of the

warring and inter-tribal fractions it was (later) said :

"No

king is truly powerful just on his own: ten to fifteen kings follow Hammurabi of

Babylon, as many follow Rim-Sin of Larsa, as many follow Ibal-pi-El of

Eshnunna, and as many follow Amut-pi-El of Qatna (North-west Amorite

territory); but twenty kings follow Yarim-Lim of Yamhad (Aleppo).”

Hammurabi is more famous for his Code of laws which he claimed to have received from Shamash, the Babylonian god of justice. He had it inscribed on human-sized stone pillars and placed them in the towns of his realm.

Much could be said about this, but it isn’t the focus here.

Only scanty and contradictory records remain of his military exploits. Many of the dates, sequences and circumstances are vague.

At first his ambitions were stymied by the balance of power.

His first real opportunity came five years later. He had already joined an unsuccessful alliance against Larsa and then (1787 BC) took advantage of the weakness of Isin to turn against former allies to conquer Uruk and raid Isin.

Unfortunately, his raid on Isin brought him into direct conflict with Rim-Sin.

Rim-Sin was Larsa's greatest king and in the process of of taking possession of Isin and some of its former allies. Hammurabi was driven back and lost the dynasty’s original capital, Kisurra, which later became independent.

The events leading to Hammurab's great breakthrough began many years later with the death of Šamši-Adad I (1776 BC, MC) the great king of the KoUM.

After that the chickens came home to roost for the man’s successors.

One of his two sons very soon lost Mari (1775 B.C) to its exiled prince Zimri-Lim (with help from Yamhad). Zimri-Lim remained beholden to Yamhad and called its then king 'father'. As soon as he regained Mari, Zimri-Lim had to fight factions within his own tribe, after which he concentrated on modestly extending his kingdom to the North turning it into a strong and wealthy kingdom.

The other son of Šamši-Adad I, Ishme-Dagan I, was in charge of the region which would later become Assyria. He was a highly competent ruler and general but found himself pressed when Eshnunna rebelled 3-4 years later (1771 BC) and began to regain territory it had originally lost to the father.

Hammurabi had already expanded his kingdom East and a little north which gave him a contested border with Eshnunna, and he joined in support of Ishme-Dagan I whose father once had taken refuge in Babylon.

Over the next 5 or 6 years, Ibal pi’el II of Eshnunna found himself fighting on two fronts.

This lead him to make an alliance with the Gutians and his old allies the Elamites which gave him the command of a truly immense army: 12,000 of his own troops, 10,000 Gutians and a large expeditionary force of Elamites.

More likely though, the Elamites (under the command of their great general Kunnam) had the greatest control over the combined force and Ibal pi’el II found himself increasingly a hostage to his Elamite allies.

The Elamites began by betraying the Gutian princess, Nawaritum, who really wanted to attack Larsa. They took her army off her, probably with promises of rich plunder, and headed north. She disappeared form history.

While they had a huge army, they still had a second front against the Babylonians and Ishme-Dagan I (and Hammurabi) proved to be a clever adversaries.

Ishme-Dagan I felt the brunt of their push but he made several local alliances and Assyria had regions that were difficult terrain for chariots and armies of that time to conquer.

In the far north it is mountainous with well watered plains south of this. Going further south there are marshes, before giving way to the more familiar arid regions of Mesopotamia.

As their ‘Assyrian’ campaign slowed, the Eshnunnites (or more likely Kunnam) next betrayed their ally Mari by raiding their settlements, opening a third front for them.

Yamhad hurried troops to the aide of Mari.

Facing the Elamites and Eshnunnites was a powerful but somewhat unwieldy alliance.

The Babylonians, (Amnanum tribesmen) were allied with Ishme-Dagan I ( a more nomadic tribe).

The Amorites from Mari were Banu-Simaal tribesmen with Yamhad tribes-men helping them.

Ishme-Dagan I was now nominally on the same side as Zimri-Lim of Mari and those two definitely didn't get on!

There was likely to be other ethnic groups and factional interests, but Hammurabi still managed to take control of the alliance and mold it too his will. He was senior in age, he was an experienced and capable general and he had a very dominating personality. Besides, he was the only one friendly with all of them and he was the only king in the combined force (until Ishme-Dagan I joined them).

Still it must have been an interesting planning group with so many fractions, especially when Hammurabi invited Ishme-Dagan I to join them in the command tent!

But things were going to became even more complicated.

The Elamites, clearly unhappy with what they and achieved in terms of plunder and territorial gains turned on Eshnunna (which had been independent or semi-independent for some time).

This meant that the diminished Eshnunnites were now battling the Elamites on another front, but they couldn't stop them seizing Eshnunna and killing their king in 1765 BC.

Hammurabi continued to manage what must have been an unruly alliance by the use of persuasion, threats and bullying. He even got his old enemy , Rim-Sin of Larsa, to send him troops to evict the Elamites and incorporated some surviving Eshnunnites into his Grand Army.

He finally evicted the Elamites from Eshnunna and Mesopotamia in 1764 BC but he didn’t get all he wanted.

He wanted to take control of Eshnunna himself or put his own client king on the throne but the army chose a man called Ṣillī-Sîn.

We don't know a lot about Ṣillī-Sîn. He may have been an Eshnunnite. He was described as a ‘modest section leader in

the army’ which might be a nod to the old Sumerian penchant for understatement.

What we

do know is that he was very wary of Hammurabi

and/or whatever alliance he was offered but he eventually accepted it and

married one of Hammurabi’s daughters.

It was

then that Hammurabi showed his true colours.

On the

flimsiest of pretexts, he took whatever of his ‘grand army’ that would follow

him against Rim-Sin of Larsa, claiming

he hadn’t sent enough troops to help fight the Elamites.

During a six month campaign, he formed an alliance with Nippur and Lagash to help capture Isin and Uruk but then turned on his two new allies and captured their cities.

This became a pattern for Hammurabi.

Driven by power and greed he would make alliances and then break them as soon as they no longer suited him.

He

conquered Larsa in 1763 BC after a siege of several months, capturing and murdering Rim-Sin, which left no one and no force in the south that

could oppose him.

In 1762

BC he returned to the north to attack his new ally Ṣillī-Sîn, capturing Eshnunna

in 1761 BC after an epic battle that involved 12,000 men on each side (presumably killing the new king).

In Autumn of the same year, he moved to attack and murder his long term ally Zimrî-Lîm of Mari. It is possible that Zimrî-Lîm had joined Ṣillī-Sîn in defending Eshnunna but his duplicity was amazing.

This left him free to attack Ishme-Dagan I but this time he faced a skilled and determined opponent resulting in a prolonged campaign.

Ishme-Dagan I was eventually forced to surrender with an unknown fraction of his kingdom remaining to him and pay tribute to Babylon.

During this time Mari revolted (1759 BC).

Mari had been a wealthy trading kingdom and its palace was the envy of the region. This time Hammurabi returned to completely destroy the city so it could never rise again.

In just a few years, (1755 BC) , Hammurabi was the undisputed master of Mesopotamia. Only Yamhad and Qatna maintained their independence.

1.

They didn't get the people to love them.

It should have been a glorious triumph. Hammurabi should have had control of an incredibly powerful and rich Empire

Later Babylonians deified him, seeing him as a God and a great king. After all, he had made Babylon and its God Marduk great throughout Mesopotamia (and who doesn't like a triumphant conqueror?)

But the people he conquered saw him very differently.

He was treacherous, a liar, a bully and a despot.

His ‘clever’ administrative reforms were built upon what many others such as Rim Sin of Larsa had done and his code of laws was built on existing Sumerian laws.

More importantly, he did not manage to make his newly conquered people love him, or his successor.

As had

been demonstrated several times before, Sumer would only unite behind a Lugal they admired and respected. Try to force them and they would only revolt.

By the time Hammurabi was finished conquering his empire, he had spent the last fourteen years of his reign almost continually fighting wars.

He was old and sick. Samsu-Iluna, had already taken over many of the responsibilities of the throne and assumed full reign in 1749 BCE.

There

was no problem with Samsu-iluna’s military abilities but when trouble broke

out, there were just too many fires to put out.

Around 1741 BC Rim-sin II , a nephew of Rim-sin of Larsa, rebelled. A total of twenty six cities including the once powerful Eshnunna joined him.

It took several years to put down this revolt but it was only a few years later

when another pan-Sumerian revolt broke out, this time more successful. It established the somewhat enigmatic Sealand Dynasty in the far south of Sumer which was destined to outlast Amorite

Babylon.

And while Samsu-iluna’

was distracted by the first revolt, Assyria descended into

chaos and civil war which removed the Amorite rulers (clients of Babylon) in

favour of a new Akkadian (local) dynasty.

2. Killing all the Geese that would have laid Golden Eggs for them

Mesopotamia was a very rich region. The first Babylonian Empire should have been very rich and powerful, but

it destroyed much of what it conquered.

The records in the cities of Ur, Uruk, Larsa, Nippur and Isin progressively ceased during Samsu-iluna's reign and archaeological records show these cities became largely or completely abandoned for hundreds of years, until well into the Kassite period.

Great cities like Larsa and Mari never recovered. The trading city of Eshnunna was devastated and, while it would eventually recover, it was never great again.

Some archeologists have speculated that this was due to Amorite mismanagement, that the native Sumerians deserted the Amorites for the native Sealand Dynasty in the south. Whatever the truth of this part, the main reason was just how destructive Amorite rule was for its occupied lands.

The Babylonian’s favourite form of warfare was to construct fortified dams across a city’s water and irrigation canals either depriving it of water or releasing the water all at once to cause a flood.

This was highly effective, but

incredibly destructive in Sumer which only survived through its canals. The Babylonians never

returned themselves to repair the damage, leaving any surviving locals to do that.

And, once

they had conquered the city they would loot it and tear down its defensive

walls. This left their conquered territory defenceless in the face of Elamite,

Kassite and Amorite armies and slaver raids that followed.

In the end of his reign Samsu-iluna was only left with a kingdom that was only fractionally larger than the one his father had started out with 50 years before.

He did have control of the Euphrates up to and including the ruins of Mari and its

dependencies and whatever was left of a much diminished Eshnunna which also suffered

a catastrophic

flood in 1755 BC.

The Fall of Babylon

After

fifty years, the (first) Babylonian Empire continued only in name. Future kings

became defensive and inward-looking.

Mesopotamia had a (mostly) peaceful influx of skilled farmers.

Sumer had the Kassites (thought to come) from the Zagros region.

Assyria, Yamhad and Anatolia had Hurrians coming

from the Caucasus.

Yamhad

filled some of the void caused by the destruction of Mari and eventually

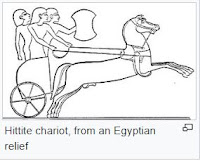

absorbed their rival Qatna but the last great Amorite kingdom was to become threatened by the rise of the Hittites who had begun uniting Anatolia under a

single dynasty.

Hattusili I (1650–1620 BC) campaigned extensively against Yamhad and its allies.

He bequeathed his empire to his grandson Mursili I who finally conquered a much weakened Halap (Aleppo) and then took his troops on an epic march all the way south to sack Babylon (1595 BC).

Though more modest in size relative to the other Babylonian Empires, it was easily the longest lasting, lasting through till 1155 BC., almost six hundred years.

I also write Epic Fantasy set in ancient times and exotic locations

Please check out my Amazon Authors page here or at your favourite e-book store.

My first book : 'The Elvish Prophecy' is free. Universal link Click Here or Amazon Click Here